You are bored by the idea of networks and connections. You yawn at the thought of BIG DATA. You wonder about the absence of creative space—the space where the random firing of a human brain tipsy on red wine might provide you something beautifully irregular and unexpected.

Non-Fiction Words by K.W., Spring/Summer 2014

*

Google your favorite writer.

No, not the one with the monthly staple-bound zine who works at Whole Foods. A famous one. Google your favorite famous writer. Dead or alive, it doesn’t matter. Just make sure she’s famous.

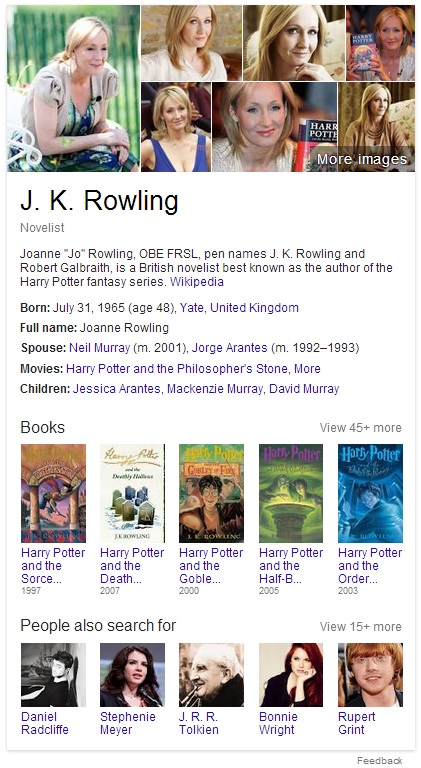

The first thing you’ll notice is all of her images.

And so now you scroll down a bit. On the left are the latest articles or news bits about your writer—her book tour, her death, an English professor’s revisionist biography. But on the right, under the images, notice now, if you will, the biographical snippet from Wikipedia; the list of major demographic facts—birthdate, awards, education; the noteworthy bibliography; and finally the “People also search for.”

People also search for.

And it is here—at the People also search for—that you see all the other writers’ names.

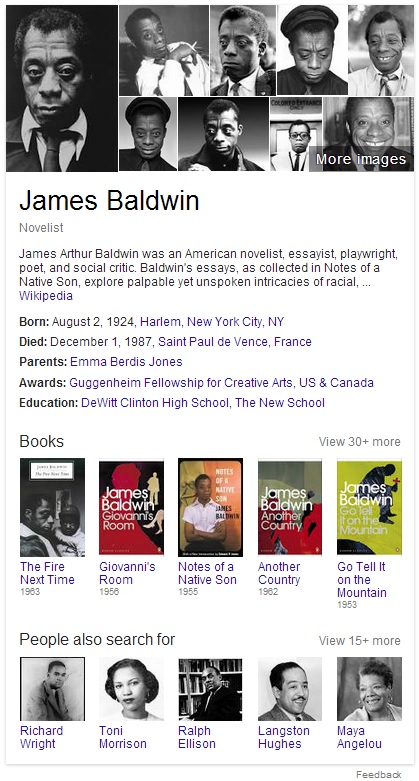

Well, usually they are other writers, sometimes they are just others, not writers. Four things are sometimes true: they are other writers (usually) whose work resembles the style (maybe) or politics (probably) or cultural background (read: race and gender; almost always) of your writer.

How nice, how nice! Google has provided you with other writers to read and love, other writers who share those many things in common with your writer. But then you remember: People also search for. And then you think: this is not Google’s doing, per se, but the doing of countless other people. You imagine other people, at home in boxers or out in trendy cafes, also searching for their favorite writers. You then multiply this image and begin to imagine an abstract mass of you—you are the people-who-also-search-for. There’s a comfortable collusion here, a feeling of contributing to some great scheme to search for the best writers in the world and all the other writers they might resemble.

But all of a sudden, you are reminded of Amazon, and how often you disagree with the reviews of other people. And also you are reminded of every comments section you have been unfortunate enough to glance at. How many silent hours you have wasted disagreeing with other people on the Internet!

You are angry.

But just who the hell are these people-who-also-search-for?

You have heard that Google has an algorithm for this sort of thing. You bet that some people-who-also-search-for are given more weight than others in determining which writers end up parked, in square images, next to your favorite writer. How undemocratic. But then, do you even want democracy here? You are the kind of person who reads the New Yorker and Michicko Kakutani to figure out what literature to get your hands on next. No, no, not democracy. You want oligarchy and clarity. You want to be able to respect and know your tastemaker.

You have questions, questions for the people in charge. And all of a sudden you’re not so certain anymore you agree at all with the writers who have been listed next to your favorite writer.

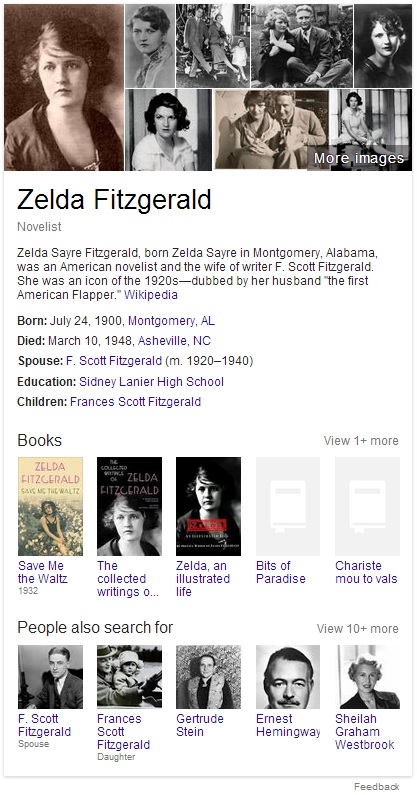

For example, what kind of injustice is this that Zelda Fitzgerald cannot escape her husband, even now in death and on the Internet?

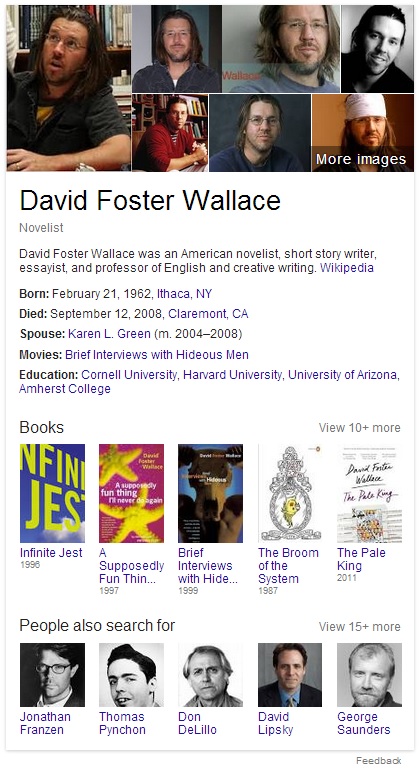

And god, what about diversity? The homophily of this thing annoys you. Of course searching for David Foster Wallace would return to you Jonathan Franzen and George Saunders.

And though she may not be “Literary,” J.K. Rowling surely deserves to be not associated first with Daniel Radcliffe.

You are bored by the idea of networks and connections. You yawn at the thought of BIG DATA. You wonder about the absence of creative space—the space where the random firing of a human brain tipsy on red wine might provide you something beautifully irregular and unexpected. Rather, here, you just have a simple computer amassing the collective wisdom of a mass of people. When you look at a mass of people, you don’t see the deviant patterns. And how boring life becomes without a little deviance. And also, and also, let’s not forget that the crowd often gets it wrong. Just now you smirk at the term “collective wisdom”—an oxymoron if there ever was one.

And you are no moron.

Just now you notice this thing, in small light grey lettering, bottom right—“Feedback.” You click. This is your chance, you realize, to set the record straight, to tell all the other people-who-also-search-for just how wrong they are in their associations and additional searches. And so you click away.

*

K. W. writes and consumes.

Images: All from Google searches